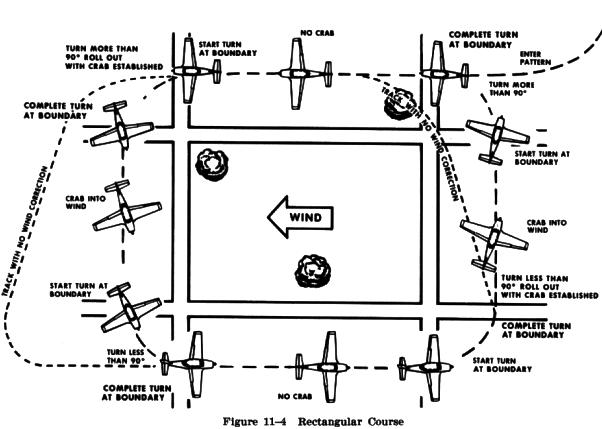

| Rectangular Course

The "rectangular course" is a practice maneuver in which the

ground track of the airplane is equidistant from all sides of a selected

rectangular area on the ground. While performing the maneuver, the altitude and

airspeed should be held constant. For this maneuver, a square or rectangular field (or an area

bounded on four sides by section lines or roads), the sides of which are

approximately a mile in length, should be selected well away from other air

traffic. (Fig. 11-4). The altitude flown should be approximately 600 to 1,000

feet above the ground (the altitude usually required for airport traffic

patterns).

Although the rectangular course may be entered from any

direction, this discussion assumes entry on an upwind heading. Simultaneously, as the wings are rolled level, the proper drift correction must be established with the airplane crabbed into the wind. This requires that the turn be less than a 90 degree change in heading. If the turn has been made properly, the field boundary will again appear to be one-fourth to one-half mile away. While on the crosswind leg the crab angle should be adjusted as necessary to maintain a uniform distance from the field boundary. As the next field boundary is being approached, the pilot should plan the turn onto the downwind leg. Since a crab angle is being held into the wind and away from the field while on the crosswind leg, this next turn will require a turn of more than 90 degrees. Since the crosswind will become a tailwind, causing the groundspeed to increase during this turn, the bank initially must be medium and progressively increased as the turn proceeds. To complete the turn, the rollout must be timed so that the wings become level at a point aligned with the crosswind corner of the field just as the longitudinal axis of the airplane again becomes parallel to the field boundary. The distance from the field boundary should be the same as from the other sides of the field. On the downwind leg the wind is a tailwind and results in an increased groundspeed. Consequently, the turn onto the next leg must be entered with a fairly fast rate of roll in with relatively steep bank. As the turn progresses, the bank angle must be reduced gradually because the tailwind component is diminishing, resulting in a decreasing groundspeed. During and after the turn onto this leg (the equivalent of the base leg in a traffic pattern) the wind will tend to drift the airplane away from the field boundary. To compensate for the drift, the amount of turn must be more than 90 degrees. Again, the rollout from this turn must be such that as the wings become level, the airplane is crabbed slightly toward the field and into the wind to correct for drift. The airplane should again be the same distance from the field boundary and at the same altitude, as on other legs. The base leg should be continued until the upwind leg boundary is being approached. Once more the pilot should anticipate drift and turning radius. Since drift correction was held on the base leg, it is necessary to turn less than 90 degrees to align the airplane parallel to the upwind leg boundary. This turn should be started with a medium bank angle with a gradual reduction to a shallow bank as the turn progresses. The rollout should be timed to assure paralleling the boundary of the field as the wings become level. Usually drift should not be encountered on the upwind or the downwind leg, but it may be difficult to find a situation where the wind is blowing exactly parallel to the field boundaries. This would make it necessary to crab slightly on all the legs. It is important to anticipate the turns to correct for groundspeed, drift, and turning radius. When the wind is behind the airplane, the turn must be faster and steeper; when it is ahead of the airplane, the turn must be slower and shallower. These same techniques apply while flying in airport traffic patterns.

|